Luck. It seems to be a universal concept, found in every human culture. There are blues songs bemoaning the fact that, “if it wasn’t for bad luck, I wouldn’t have no luck at all.” People talk about how their luck’s been so bad they’d have to look up to see the belly of a snake. Then there are other people who seem to live enchanted lives, lives where one good thing after another happens to them for no apparent reason other than they’ve got really good luck.

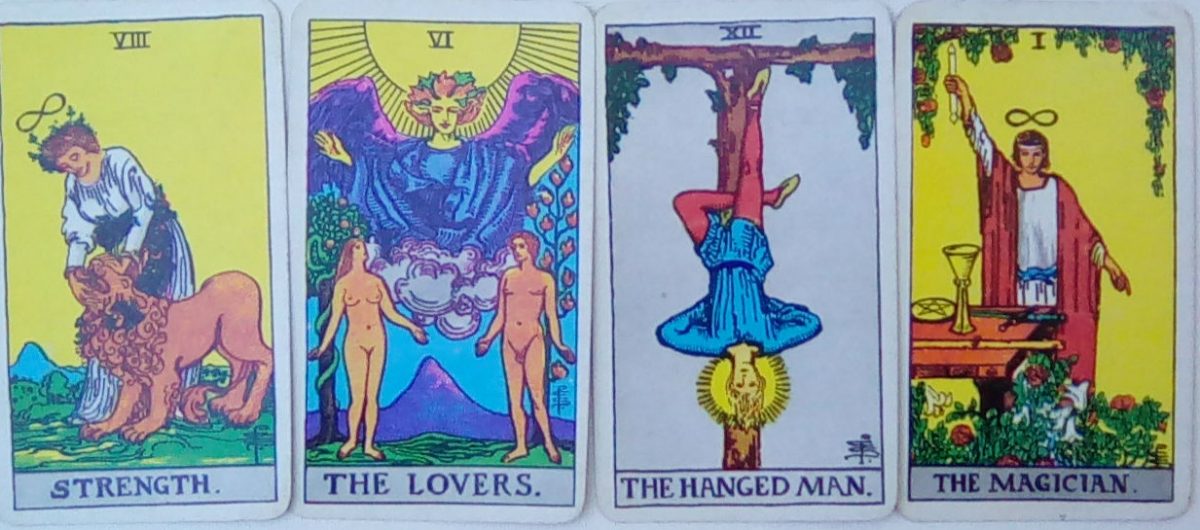

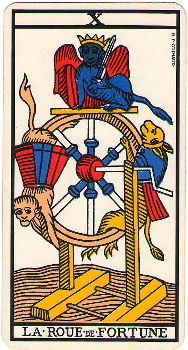

The Wheel of Fortune Tarot card is obviously about luck, but the modern, Waite Deck depiction of it is really just about good luck. It shows a wheel bedecked with Egyptian deities and surrounded by symbols of the four elements or, perhaps, the four apostles. There’s nothing threatening or scary about this version of the card.

When we look at the old, Marseilles deck version of the card, though, we see a different story. Instead of Egyptian deities, we see . . . um . . . monkey critters. Wizard of Oz flying monkeys, one perched atop the wheel, wearing a crown and wielding a sword, one being carried upward on the wheel and one being cast down by the wheel. This is really much more in keeping with that very primal perception of luck that we humans have always had about luck. It’s something kind of creepy, magical, and outside of us, outside of our control. We can never tell when a flying monkey might swoop down out of nowhere and carry us away in its nasty little talons

Humans are always trying to find a way to harness luck, to somehow bring it under our control. There are dozens of gods of good luck that we’ve worshiped through history – Hotei, Fortuna, Lakshmi, etc. – hoping that they’ll bless us with strong luck. Many people carry a rabbit’s foot or a lucky penny or have, “lucky socks,” or jeans that they favor. A lot of obsessive compulsive behavior flows out of a ritualistic quest for luck. OCDs may feel an urgent need to wipe the counter exactly seven times or wash their hands three times in order to avoid something catastrophic happening. Most of us were taught the basics of avoiding bad luck as children. Don’t step on a crack or you’ll break your mother’s back. Don’t walk under a ladder. Don’t break a mirror. Oh, shit, it’s a black cat!

The older Tarot card shows both good luck and back luck – one monkey is rising on the Wheel of Fortune and one is descending. The two phenomena seem to go together, to be attached, one rising from the other. The second verse of the Tao Te Ching alludes to this when it says:

Once we know beauty, we know ugliness.

Once we know good, we know evil.

High and low, long and short—all these opposites support each other and can’t exist without one another.

That duality, that sense of opposites always going together, seems to apply to everything on the material plane, including luck. Good luck seems to give way to bad luck and bad luck gives way to good luck, or that’s the way that we conceptualize it.

Eckhart Tolle suggests that, at least to some extent, it really is just about the way that we conceptualize it. Many times, what we view as bad luck is just the end of a cycle. Everything grows and then it diminishes and then it grows again. We don’t view plants dying at the onset of winter as a tragedy, but we do view humans dying at the end of their incarnations as tragic.

Louise Hay has much the same view of the ends of relationships. When we break up with someone or we get a divorce or our partners die, it feels like a horrible, painful tragedy. It feels like bad luck. She suggests viewing it instead as a sort of a graduation. At the point the relationship ends, it means that we’ve learned everything we were supposed to learn from the dynamic of that relationship and it’s time to say, “thank you for the wisdom,” and move on.

The Law of Attraction people tell us that good luck and bad luck can actually be learned behaviors, patterns that we get into that, “attract,” more of the same. If we can learn how to maintain a positive, healthy outlook on life, we tend to attract positive, healthy people and things into our lives. In the same sense, if we see life as a terrible, crappy experience where we’ve got nothing but bad luck happening, that’s what we attract. Even worse, we attract people with the same negative vibes and then we get to deal with their shit in addition to our own. That can go a long way toward explaining why some people always seem to be lucky and some people seem to have a curse on them.

Pema Chodron said that life is all about being constantly thrown out of our nest. Constantly forced to give up our security and adapt to new experiences. Quite a bit of what we call, “bad luck,” is that simple, elemental human experience of not wanting things to change. We envision an idyllic, static existence where nothing new or challenging ever happens to us because change is scary. Getting fired from our jobs, losing our partners, having to move out of our houses – these are all bad luck because they’re changes that we don’t want.

There are a couple of things worthy of noting about that, though. The more that we resist change – the more that we say, “no,” to the end of a cycle – the more dramatic that change is eventually going to be. It’s almost like an explosive force that just keeps getting more and more powerful the longer we sit on it, until it eventually blows our existence into tiny, smoldering pieces. A small change that we resist can easily grow into a catastrophe that we could have avoided.

The other thing to note is that good luck so often grows out of bad luck. After we’ve had a period of seriously rotten luck, we frequently find our lives being showered with blessings of all sorts. It could be that, as the Taoists assert, good luck is attached to bad luck and one inevitably gives rise to the other. Or, as Tolle said, perhaps we’re just ending one cycle and plowing the dead weeds under the ground to make room for the new growth.

That can make a huge difference in how we experience those periods of, “bad luck.” We can realize that The Wheel of Fortune is a wheel that’s constantly turning and that we’re never stuck in one place. It just feels like it. Being thrown out of the nest may feel incredibly uncomfortable emotionally. It may be terrifying. It may feel like horrible luck. But it’s the only way we learn how to fly.

Dan Adair is the author of, “Just the Tarot,” available on Amazon.com at a very reasonable price.