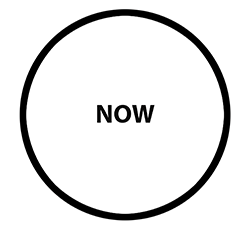

I love Eckhart Tolle’s statement that, “it’s never not now.”

It’s totally true, but we really have to bend our minds a lot to get into that space. It’s not too difficult intellectually, because we can look at it rationally and realize that there really is no past (except in our heads) and there really is no future (except in our heads.) I mean, it’s not like there’s some Past Land, like a Disney adventure ride, that we can go visit. IT DOESN’T EXIST. Ditto with the Future, because all that it really consists of is our projections of what we think will probably happen. Maybe. Could be.

Despite that, we humans spend a MASSIVE amount of our lives Time Traveling to the future or the past and very little time in the Now. Put another way, we use a lot of our mental space living in something that doesn’t even exist and, as a result of that, we spend very little time existing in the space that actually does exist. We’re so bad at living in the Now that we actually have to take mindfulness classes to learn how to do it.

So how in the hell did this sorry state of affairs come to be? We should find the person responsible for this and give him a good thrashing.

Oddly, the answer seems to be that it was our old buddy, Organized Religion, that did it. In the Tarot, organized religion is represented by The Hierophant and The Hierophant has rules and regulations that we’re all supposed to bend our knees to. One of his Big Rules is about time and it says, “There isn’t enough of it.”

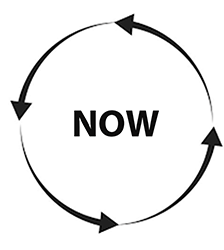

Now, probably the original way that humans experienced time was sort of like this:

There was just a big NOW, with no concept of the past or the future. We just sat there in the bliss of the present moment soaking it all in. Or it might have been a little bit more like this, where one NOW moment just led into the next NOW moment. No concept of past or future, just NOW.

That’s much the way that babies seem to experience time. They can lie there for hours staring at a sunbeam and not get worked up at all about what the sunbeams are going to look like tomorrow or worry about what the sunbeams were like yesterday.

At a certain point in our evolution, our experience of time probably shifted more into the model we see with the Wiccan Wheel of Time.

We started to notice the cycles of the Moon and the passing of the seasons. There would have been some recognition of certain times of the year but not a great deal of worry about it. The Native Americans of the Northwest expressed it in terms of activities. “This is the time when we gather berries. This is the time we catch salmon. This is the time when we plant seeds.” And so on.

Still, there was none of the huge anxiety that we seem to feel about time today. Tribal people didn’t sit around their camp fires filling in dates on a calendar or trying to figure out how to, “use their time more productively.” They just did what they needed to do when it was the right time of the year to do it. “Hey, I’ll bet some fried salmon would go great with these blackberries! We should probably stack up a little fire wood while we’re at it because it’s going to get cold sometime soon.”

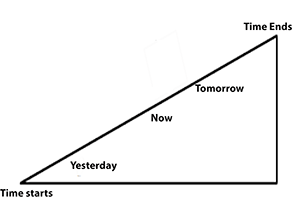

Unfortunately, while the Native Americans were sitting around having fish fries and enjoying their blackberry cobblers, humans in the Middle East were coming up with an entirely different concept of time, which historians refer to as the, “inclined plane,” model. The reasoning behind this model of time ran very much like this:

- – If time exists, then there must have been a BEGINNING of time, because . . . you know . . . there just must have been.

- – And if someone, “started,” time, then it must have been someone who was OUTSIDE of time and that would be someone who was eternal and that would be God.

- -And if there was a start to time, then there must also be a stop to time, which is when the world ends and God will do that, too, so I think we should call it The End Times.

Okay, so it wasn’t the best piece of human thinking that we’ve ever seen, but they didn’t have Google in those days so they couldn’t really look things up. It also represents a HUGE shift in human perception and one that we’re still suffering from today. All of a sudden, time looks like this:

So time has suddenly become a quantity, rather than a quality. It begins and it ends. We can measure it, we can put it on calendars, we can plan it, we can carry it around on the daily planners of our phones. Shazam! – we have the concepts of the past and the future, of yesterdays and tomorrows. We see this notion of time-as-a-quantity deeply ingrained in our languages.

I need to SPEND some time on that.

I’m not sure I want to INVEST that much time in it.

Time’s a WASTING.

This should be a real time SAVER.

I need to ORGANIZE my time.

We’re RUNNING OUT of time.

I’ll PAY you for your time.

When we look at all of those statements, the basic message is that THERE ISN’T ENOUGH TIME, goddamnit! Which, of course, is ridiculous, because there’s all the time in the world. Literally.

We’ve been so totally hypnotized by the religious concept of time that we can’t imagine a world without it. We’ve devolved from that perfect bliss of a baby tripping out on the sunbeams into beings who are missing our own lives because we’re constantly living in the past or in the future. The only cure for it seems to be to re-train our brains back into living in the NOW through mindfulness meditations and living mindfully.

I mean, you know, if we can schedule the time for that. I’ll have to look at my calendar . . .

Just a reminder that there is ALWAYS time to read my ebook, Just the Tarot, and it’s still available, dirt cheap, on Amazon