“I’ve known several Zen Masters and they were all cats.” – Eckhart Tolle

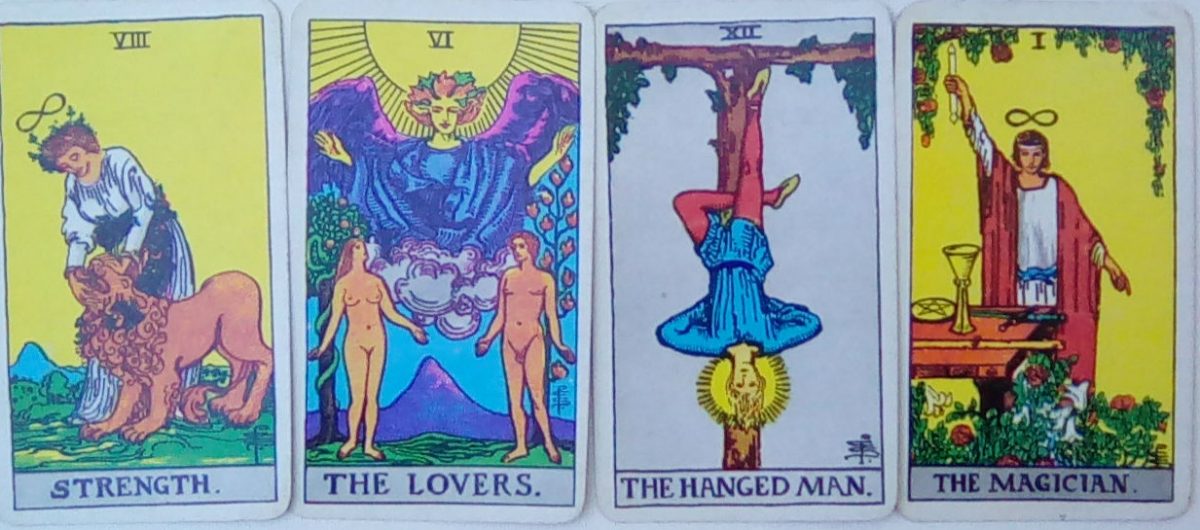

The image in The Fool tarot card shows a person dancing with joy at the edge of a cliff. It’s meant to portray a Soul that’s so fully in the Flow that, even if she were to dance off of the cliff into thin air, she wouldn’t fall. It’s a beautiful card, but we seldom take much note of the little dog that dances right along with The Fool.

In her book, “Animal Soul Contracts: Sacred Agreements for Shared Evolution”, Tammy Billups addresses the idea that animals come into our lives for specific reasons and they’re often instrumental in helping us to recover and evolve. As she puts it, we have a Soul Contract with our animals. We heal them and they heal us.

She tells the story of a man who was living alone when a stray dog suddenly showed up on his doorstep. He took the dog in and they formed a strong, loving bond. The one problem was that the dog developed terrible separation anxiety and suffered greatly whenever his new owner had to leave the house.

He finally contacted Ms. Billups in the hope that she could work with the dog and help it to feel more secure. In the course of treating the dog, though, the man had a sudden epiphany: every relationship he’d ever had ended up with his lover walking away from him. He had severe abandonment issues of his own and so he’d attracted an abandoned dog. He started therapy and, as he learned to deal with his own fears of abandonment, the dog healed from its separation anxieties.

She posits that animals – and particularly that class of animals that we refer to as our, “pets,” – have a very deep and ancient Soul connection with human beings. They not only mirror who we are, as the dog did with the young man, but they also point us toward a better way of existing in the world.

One thing that they provide to us abundantly is pure, unconditional love. Getting that kind of love as an infant is vital to the development of a healthy, well adjusted human being. Sadly, though, we have a lot of people in our world who were beaten more than they were hugged as children. We emerge as adults who are convinced that (a) we can’t be loved; (b) somehow it’s our fault, rather than the fault of our crazy parents; and (c) it’s never safe to reach out to other people for love.

And then a puppy or a kitten shows up in our lives and loves us unconditionally. The dog or the cat doesn’t give a flip about how smart we are or how we dress or how much money we have or any of the other parameters we may find in human relationships. They just love us, totally and unconditionally, for who we are. And, yeah, we learn that lesson on a deep Soul level: it’s safe to love and to receive love. They fill that hole in our hearts that’s been there since we were babies.

Another example that Ms. Billups gives is that highly empathetic people (and particularly empaths) will tend to attract highly empathetic animals. We run into that sometimes with an animal that literally seems to be peering straight into our Souls when it looks at us. There’s a sort of a tickle in our energy systems and a voice that says, “This dog somehow understands exactly who I am and what I’m feeling.”

The common bond is that both animals and empathetic people are primarily, “feelers,” rather than just thinkers. We exist on that energy level of emotions and almost instantly perceive the hidden vibrations in another being. And the, “training,” that we receive from that kind of an animal is to learn to keep our own vibrations as loving and kind as possible because they’re feeling them just as much as we are.

Which brings me to the part of Ms. Billups discussion that really blew me away, which is emotional support animals.

We’ve seen a fairly substantial increase in the presence of emotional support animals as a result of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Many of the troops were returning home with severe PTSD and social anxiety. Psychologists found that pairing them with animals – usually dogs – helped to soothe their nervous systems and allowed them to interact more peacefully in social settings.

It makes sense, even on a superficial level. If we’re feeling extreme anxiety, the presence of a calm, loving animal would obviously settle us down. Ms. Billups takes that a step further, though.

She says that some animals, especially emotional support animals, are able to hold what she calls a, “transformational healing presence.” In other words, it isn’t just their presence as a trusted companion that’s calming down the person’s nervous system. Rather, these are animals that are SO evolved that they’re able radiate calmness, serenity and love out of their very core.

We can actually see that with our own eyes. The next time that you encounter someone with a support dog in a store, stop and look at the people around you. Most of them will suddenly slow down, smile, and begin to radiate calmness of their own. It isn’t just because they think the dog is cute, either. Rather, they’re walking into that energy field of a healing presence that the dog is holding and it transforms them.

There’s a lesson in there for humans, as well. It takes work – sometimes a lot of work – but we can become that same sort of a transformational healing presence in the world. Through therapy, affirmations, meditation, and working with our heart chakras, we can nurture a core energy that’s calm, loving, and compassionate.

We don’t need to develop a philosophy or a method around that. We don’t need to become gurus or convince anyone that they should behave in this way or that way. All that we need to do is to build the love in our hearts and radiate it out into the world.

One of the neat things about that is, like the support dog in the store, we can step out of all of that judgment about who’s going to receive the love. The dog isn’t standing there thinking, “Oh, that one’s a Republican – no love for him.” Or, “Uh, oh, it’s a liberal, shut down the love.” It’s there for anyone who wants to receive it, no questions asked. And if someone doesn’t want to receive it, the dog doesn’t get upset or neurotic about it – she just keeps shining that light.

So I’m going to start paying a lot more attention to the animals in my life and begin actively looking for the messages that they’re bringing me. Perhaps I’ll put my cat in my lap the next time I meditate and see if she has anything she’d like to add. I’m guessing she does.