I was just reading an article about suicide in the elderly and the author – a certified therapist with a PhD, mind you – suggested that a good preventative might be a robotic cat or dog that we could talk to and sleep with. That way, we wouldn’t be lonely and, if we weren’t lonely, we wouldn’t be offing ourselves at record numbers.

Now, if you weren’t already suicidal, the idea of having to get a little cat robot to be your best friend would surely drive you over the edge. It’s such a radiant example of NOT understanding suicide in the elderly that it’s almost breathtaking.

Here, kitty kitty! Oh, shit, her batteries are dead. Might as well just kill myself.

The, “reasons,” for elder suicide are all over the place. According to the experts, it’s because we’re lonely, or we’re socially isolated, or we’re sick, or we don’t have jobs anymore, or our spouses died, or we’re invisible in a youth-culture, or we never get touched by anyone.

My very favorite is that elderly people commit suicide because they’re . . . drumroll, please . . . depressed.

You think?

After spending several days combing through articles and studies about why elderly people kill themselves, I came to two conclusions. One – nobody really knows why. Two – nobody is very motivated to find out. From a purely dollars and cents perspective, it doesn’t make a lot of sense to social scientists to study elderly suicide because – hey! – old people are, you know, old. Why spend a ton of money studying how to keep them alive when they’re supposed to die soon anyway?

They have pretty much pinned down the people at the highest risk. The person who is most likely to commit suicide in the United States is an elderly, white, male, introvert with a family history of suicide.

Males kill themselves four times more than females. Apparently it’s one of our special skills, though it’s probably best to not note it on our resume’s. No surprise, then, that those statistics would go across all of the age groups and extend into old age.

I can also understand the factor of the family history of suicide. Perhaps that’s just a genetic predisposition to depression, but once you’ve seen suicide modeled in your own family, it’s hard to unsee it.

Introversion is a little harder to grasp, because it exists across such a broad spectrum and means so many different things to different people. About 52% of the general population are introverts but most of them are obviously not suicidal.

Researchers have been quick to make the leap from introversion to loneliness and social isolation, though. Under that model, introversion = social isolation, which = loneliness, which = depression which causes suicide.

Leaving aside the fact that those us with robotic cats are hardly lonely, other statistics would seem to refute this approach. Elderly women actually report much higher levels of feeling socially isolated and much higher levels of feeling lonely than elderly men. If there was causation from those factors, we’d expect to see the gender statistics reversed, with women killing themselves at four times the rate of men.

There’s another interesting difference we can discern when we look at a recent study from UCLA. Dig this:

“What’s striking about our study is the conspicuous absence of standard psychiatric markers of suicidality across all age groups among a large number of males who die by suicide,” said Kaplan, a professor of social welfare at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs. They found that 60% of victims had no documented mental health conditions.

In other words, the standard perception of suicide as being caused by long term mental illness simply isn’t born out. Suicidal men aren’t crazy, they’re just suicidal.

So, if elderly men aren’t killing themselves because they’re more lonely, more isolated, crazier, or more introverted than everyone else, what’s causing it?

I suspect that a large part of it may lie in another part of the description, which is, “white male.”

Of all of the many groups in the United States, there is no group that is more likely to fully participate in the toxic masculine paradigm than the Caucasian male. We have, simply by being born with white skin, more access to the education and financial resources that enable us to become completely enmeshed in the insane pursuit of money, power, and position. We abandon our own authenticity in that lifelong pursuit.

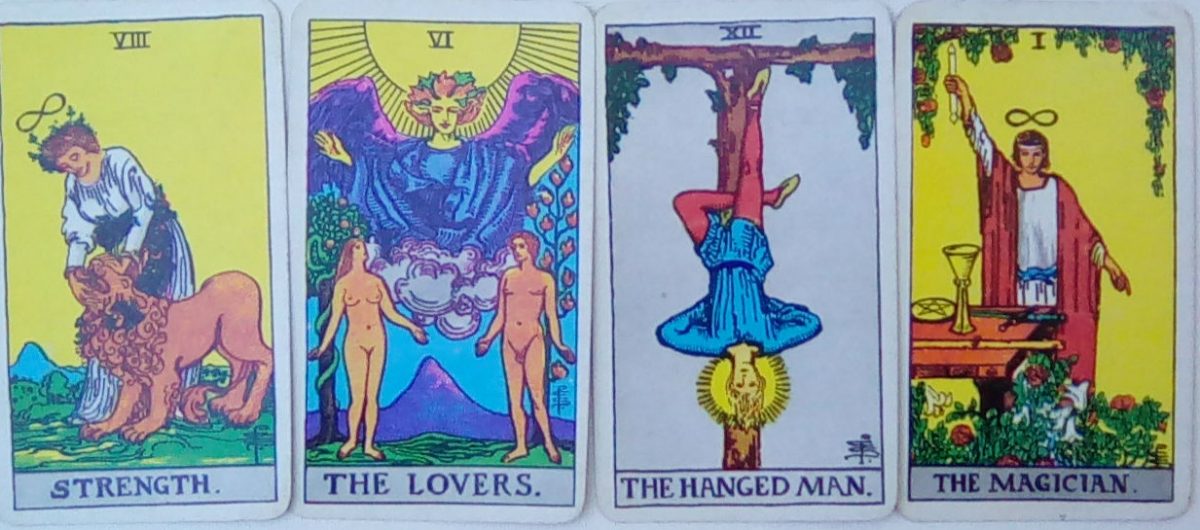

When we look at the Tarot card, The Emperor, we see the ultimate outcome of that paradigm. Yes, he’s sitting on a throne and he’s powerful. He’s also completely and totally alone, covered from head to toe in his armor. Everything around him is a blasted, sterile wasteland. No friends. No lovers. No family.

He doesn’t even have a fucking robotic cat to sit on his lap.

When we talk about toxic masculinity, we mainly frame it in terms of the negative effects that it has on women who come into contact with it. We tend to forget that it’s the men who are carrying all of those toxins around with us. And it’s killing us.

Is it likely that white American males will begin to look at the female paradigm or perhaps people of color and try to figure out why we’re killing ourselves and they’re not? Probably not. On the other hand, artificial intelligence is improving by leaps and bounds. It’s only a matter of time – hopefully a very short time – until we’ll all have robotic cats and dogs who can actually talk to us and help us deal with our emotional problems more realistically.

Here kitty kitty! I have some brand new batteries for you, sweetheart.

I am very pleased to announce that my ebook, “Just the Tarot,” is now available FOR FREE on Amazon for anyone who has a Kindle Unlimited membership. The cheapest robotic cat that they offer is $113.00 so this is just one hell of a deal.