There’s an interesting – and somewhat paradoxical – psychological principle which is that THE MORE WE BECOME OURSELVES, THE LESS LIKELY WE ARE TO BE UNDERSTOOD BY OTHER PEOPLE. That may sound a little grim, but there’s a lot of truth in it.

By way of an example, I’m a male. In a very basic sense, I have NO idea what it’s like to be a female. I can empathize with females, I can understand their political, emotional and social issues, I can be a strong supporter of feminism. But I can’t understand, on a primal level, what it’s like to be a female. There’s a whole slew of experiences in there – growing breasts, having your first period, prom dates, motherhood, etc. – that just aren’t a part of my being-in-the-world or my personal history.

I can take that up a notch and say that I’m an American male. So I would definitely NOT understand what it’s like to be an Indonesian female. Or I could say that I’m an older American male, so I would really, really not understand what it’s like to be a young Indonesian female.

The more different we are, the less we understand each other.

There’s also a very natural human drive called individuation, where we want to become separate, unique individuals. We see it most clearly in adolescents. For the first ten years of their lives they’ve been nothing more than extensions of their parents and their families. Suddenly, as puberty approaches, they want to dress differently, act differently, and explore new ways of thinking. They are compelled to differentiate themselves from their parents and if that means they get a neon nose ring to prove they’re different, so be it.

Although it’s less obvious, that drive to be, “different,” continues into adult life. In the United States, we mainly express it through our adult toys and our clothing. We talk about someone making a unique, “fashion statement,” or we’ve got a friend who drives around in a rare, restored 59 Chevy, or we raise Venus Flytraps . We take a lot of pride in our uniqueness and tend to denigrate being, “a part of the herd.”.

For some people, though, that drive to be different, to fully express themselves as unique individuals, can have a downside to it as well. The reason for that is that we also have an equally strong drive TO BE HEARD, not just to be seen. To be understood. To have meaningful conversations and interactions with other human beings who really get what we’re feeling and thinking.

As Michael P.Nichols put it in, “The Lost Art of Listening,”

“Few aspects of human experience are as powerful as the yearning to be understood. When we think someone listens, we believe we are taken seriously, that our ideas and feelings are acknowledged, and that we have something to share.”

That transaction of communicating and being understood and validated assumes that we have some common ground with the other person. The more that we have in common with the other person, the more quickly and easily they’ll understand what we’re saying. If the only language I speak is English and the only language you speak is Spanish, we’re not going to do much meaningful communicating. If you’re from New York City and I live in a small town in the mountains, we are NOT going to rock and roll.

It’s really a simple ratio: the more we’re alike, the more easily we’ll communicate. The more that we’re different, the more difficult it is to communicate.

So what happens if you’re not just different, but radically different from most people? So different that you share very little common ground?

Here’s an example from the Jungian personality types. We know that some people are introverts and some people are extroverts. The more introverted we are, the less likely we are to understand how extroverts see the world, and vice versa. Then take that up a notch by looking at an introverted personality type called the INFJ. Only one percent of the people in the world share that personality type. Take it up another notch by looking at males who have the INFJ personality type. Only 0.5 percent of the people in the world share that person’s personality.

That means that if you are a male INFJ personality type, over 99% percent of the people you meet will NOT understand how you process and view the world. That’s not a lot of common ground. That’s not even a pebble.

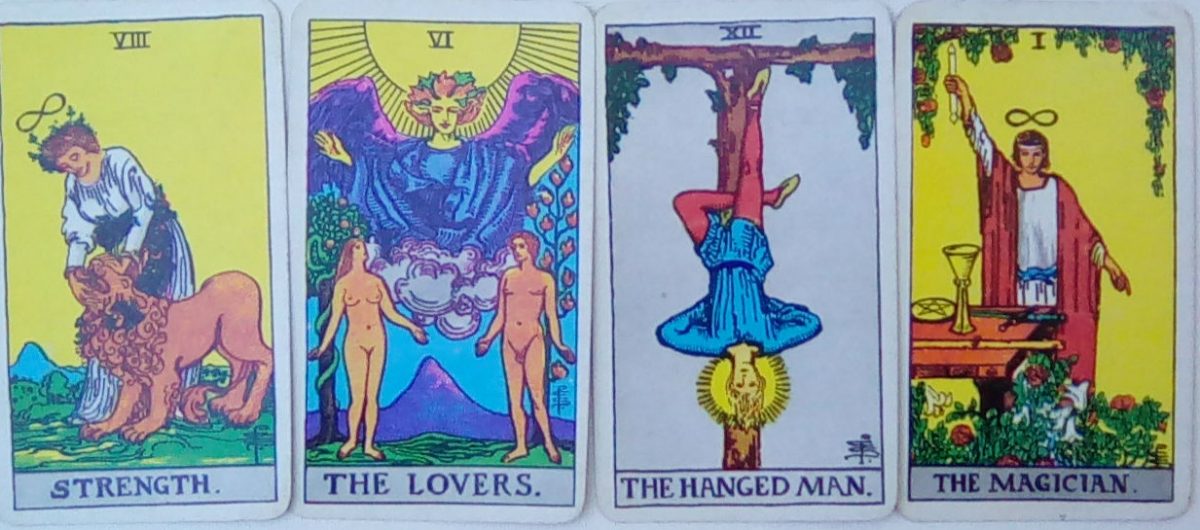

Or suppose you’ve taken a radical spiritual route such as we see in the Tarot card, The Hermit. You’ve intentionally withdrawn yourself from the world and consciously sought another path like meditation or extreme solitude. After a few years of that kind of a lifestyle, there isn’t just a minor rift between your vision of the world and the way the average person sees it, there’s a giant, fucking chasm.

The more different you are, the less people will understand you.

Now, experts tell us that there’s a sort of an arc in that process that eventually leads people who are very different back to understanding that, on a spiritual level, we’re all the same. Marsha Sinetar in her book, “Ordinary People as Monks and Mystics,” says that pursuing your true authentic self will inevitably lead to greater compassion and empathy with other people. People who are largely detached from society eventually reattach on a much deeper level.

But . . . until that happens, until we reach that point of reattachment, it can be a very painful ride. There can be the realization that people we really care about just don’t understand us. The feeling that we don’t fit in, not anywhere. There can be a terrible hunger to have just one person meet us on common ground. There can be a severe sense of loneliness, isolation, and, yes, not being heard, a despairing feeling that we will never have a real friend or lover.

Put another way, being true to yourself is not for the faint hearted. If the average person moves into an isolated cabin in the woods with no phone, no neighbors and no social media, he’ll go nuts in very short order. Being true to yourself and your unique perceptions of the world can feel very much like living in that isolated cabin, even in the middle of a very busy city.

It requires a strong ego structure. It requires the ability to enjoy emotional solitude, rather than seeing it as a curse. It takes a lot of resiliency. More than anything, though, it takes an ability to ferociously believe in ourselves. Not to criticize others or try to force them to share our visions, but to say, “I am me. I have a right to be here. I have a right to be my own unique expression in the world. I hope that someday you’ll be able to see me. I hope that someday you’ll be able to hear me. But the most important thing is that I can see me and I can hear me.”